For years, a set of concrete columns sitting adjacent to the 400 block of Cotton Street in downtown Shreveport has been a source of idle musings. There was obviously something there once, and that something would have been heavy to require such a massive support structure, but what?

For years, a set of concrete columns sitting adjacent to the 400 block of Cotton Street in downtown Shreveport has been a source of idle musings. There was obviously something there once, and that something would have been heavy to require such a massive support structure, but what?

A Vicksburg, Shreveport and Pacific locomotive

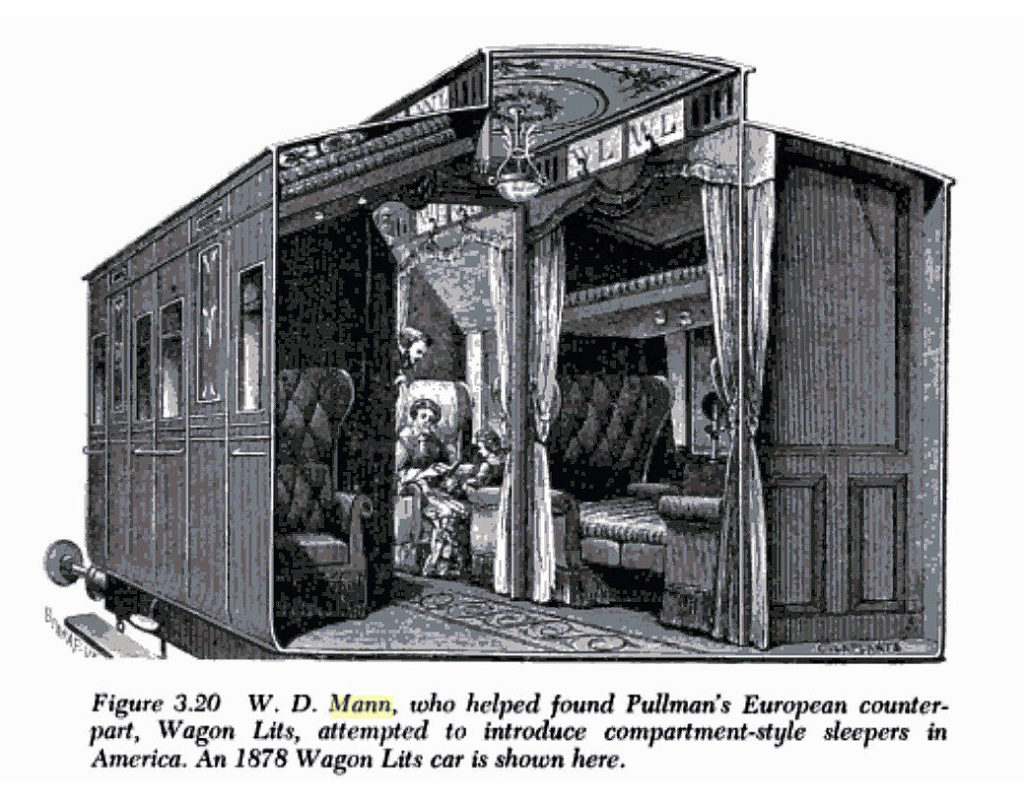

The pillars are on KCS Railroad property and sit adjacent to two sets of railroad tracks that are currently in heavy use. These tracks are in the same general area as one of the first tracks to come through Shreveport prior to the Civil War, a line of the Vicksburg, Shreveport and Texas Railroad Co., later to be named the Vicksburg, Shreveport and Pacific. This trunk line was once a part of  the Queen and Crescent Route that went from Cincinnati (the Queen City) to New Orleans (the Crescent City) and on the trains you could book a Mann Boudoir car. These luxurious cars were only available on selected trains for a short period of time; the company was later acquired by Pullman. The Mann cars were the absolute epitome in railroad travel luxury.

the Queen and Crescent Route that went from Cincinnati (the Queen City) to New Orleans (the Crescent City) and on the trains you could book a Mann Boudoir car. These luxurious cars were only available on selected trains for a short period of time; the company was later acquired by Pullman. The Mann cars were the absolute epitome in railroad travel luxury.

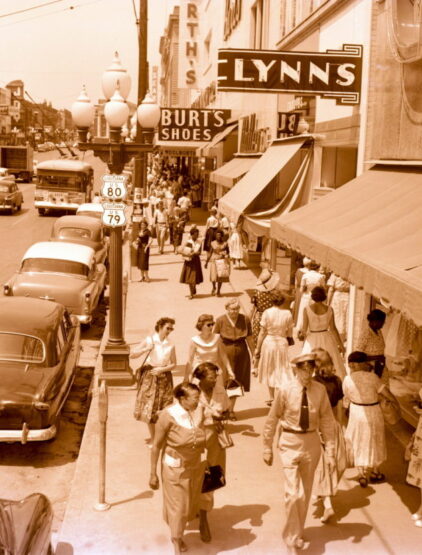

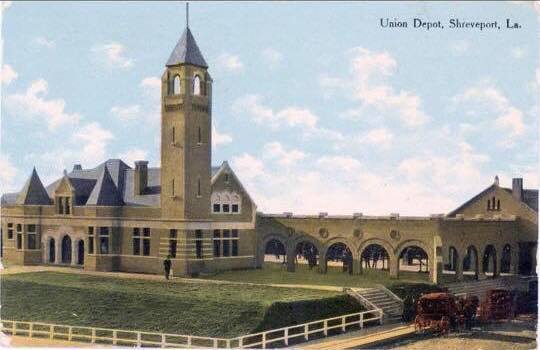

At that point in history, downtown was the local hub of railroad activities. There were train  yards, round houses, and in 1897, Union Station. Union Station was a large passenger terminal, built in the 900 block of Louisiana Avenue across from the then- Jefferson Hotel. Owned by the Kansas City, Shreveport and Gulf Terminal Co. (a subsidiary of the KCS), it was used by KCS, Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co., Louisiana & Arkansas, Illinois Central, Cotton Belt and the Texas & Pacific railroads. There was a LOT of train traffic along the Cotton Street tracks, in fact reports say between WWI and II, some 45+ passenger trains a day came through. Union Station_RRnewsletter

yards, round houses, and in 1897, Union Station. Union Station was a large passenger terminal, built in the 900 block of Louisiana Avenue across from the then- Jefferson Hotel. Owned by the Kansas City, Shreveport and Gulf Terminal Co. (a subsidiary of the KCS), it was used by KCS, Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co., Louisiana & Arkansas, Illinois Central, Cotton Belt and the Texas & Pacific railroads. There was a LOT of train traffic along the Cotton Street tracks, in fact reports say between WWI and II, some 45+ passenger trains a day came through. Union Station_RRnewsletter

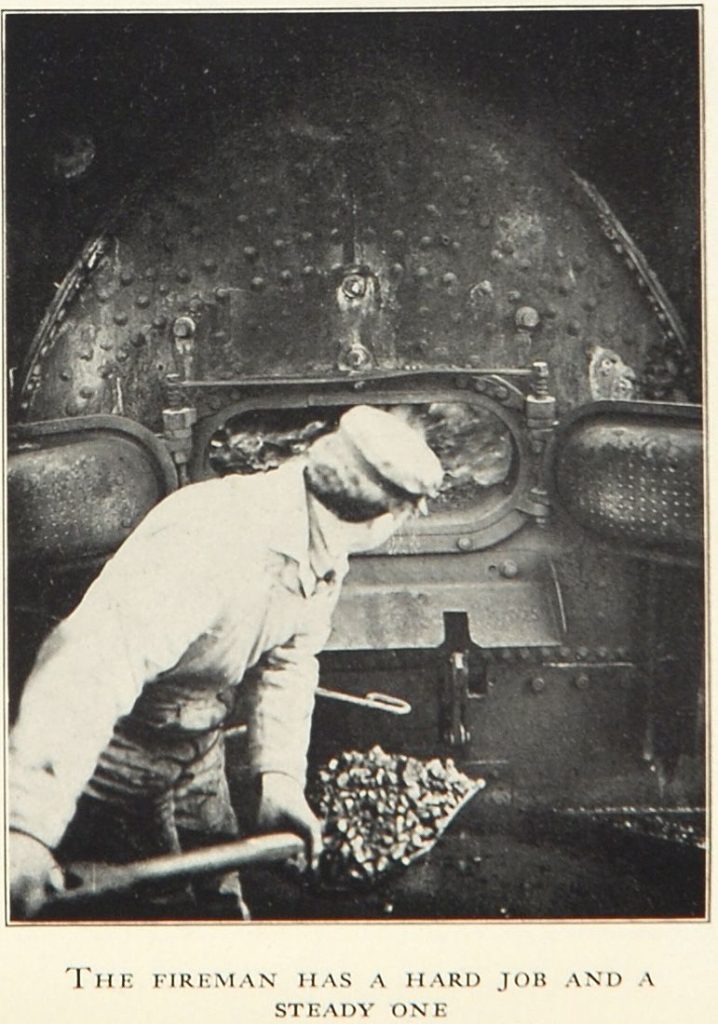

Initially, the trains that came through would have burned wood to make the steam for power. They changed to coal in about 1880, and coal continued to fuel some trains until the 1980s. The conversion to diesel or electric starting in the 1930s, but it was not an overnight change. That meant trains using the Cotton Street lines were using coal for 55

Initially, the trains that came through would have burned wood to make the steam for power. They changed to coal in about 1880, and coal continued to fuel some trains until the 1980s. The conversion to diesel or electric starting in the 1930s, but it was not an overnight change. That meant trains using the Cotton Street lines were using coal for 55  years-plus. Each train would have hauled what is called a ‘tender’, a vehicle containing its fuel, oil, and water. How often the tenders would have needed to be refueled would depend on a lot of things- the load, the train’s speed, the terrain…but some old railroad hands say a good rule of thumb is every 100 miles (water for the steam would have been needed more often, FYI).

years-plus. Each train would have hauled what is called a ‘tender’, a vehicle containing its fuel, oil, and water. How often the tenders would have needed to be refueled would depend on a lot of things- the load, the train’s speed, the terrain…but some old railroad hands say a good rule of thumb is every 100 miles (water for the steam would have been needed more often, FYI).

Side Note– One of the sections on the second floor of the old Interstate Wholesale Furniture Building at the top of Lake Street at McNeil that sits adjacent to three train tracks is covered in soot from the thousands of steam trains that would have passed by over the years. The owners enjoy allowing visitors to wipe their fingers in 100-year-old coal dust!

There has been speculation that the structure on Cotton Street was either a water station or a coal station, and it could have been both. Dave Bland of the Red River Valley Historical Railroad Society & Shreveport Railroad Museum and Marty Loschen of the Spring Street Museum both uncovered data that seems to solve this long mystery, and here it is…

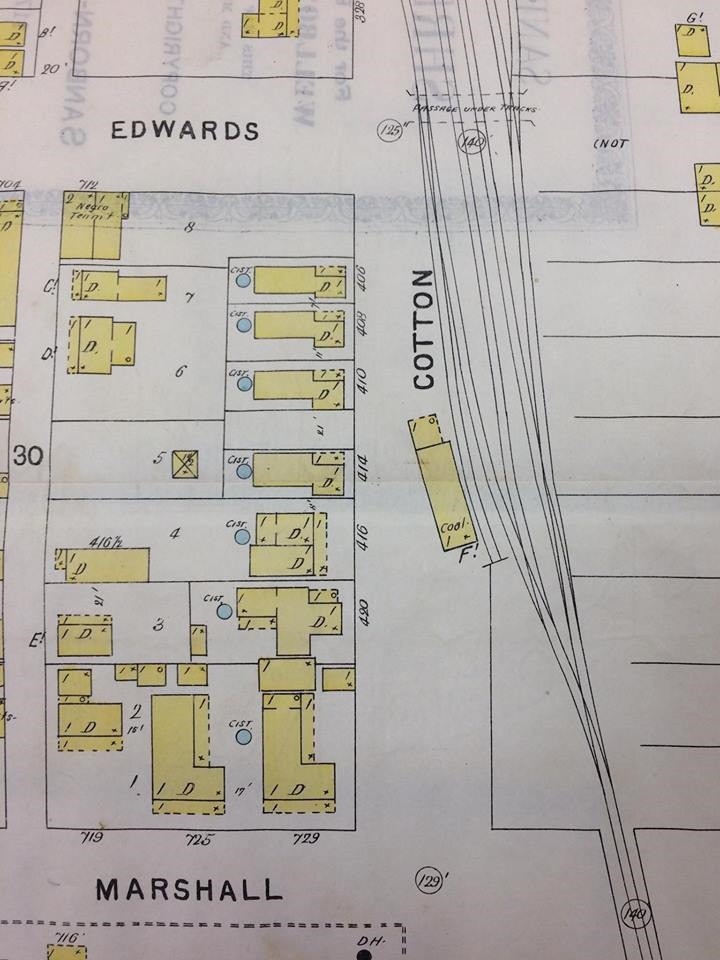

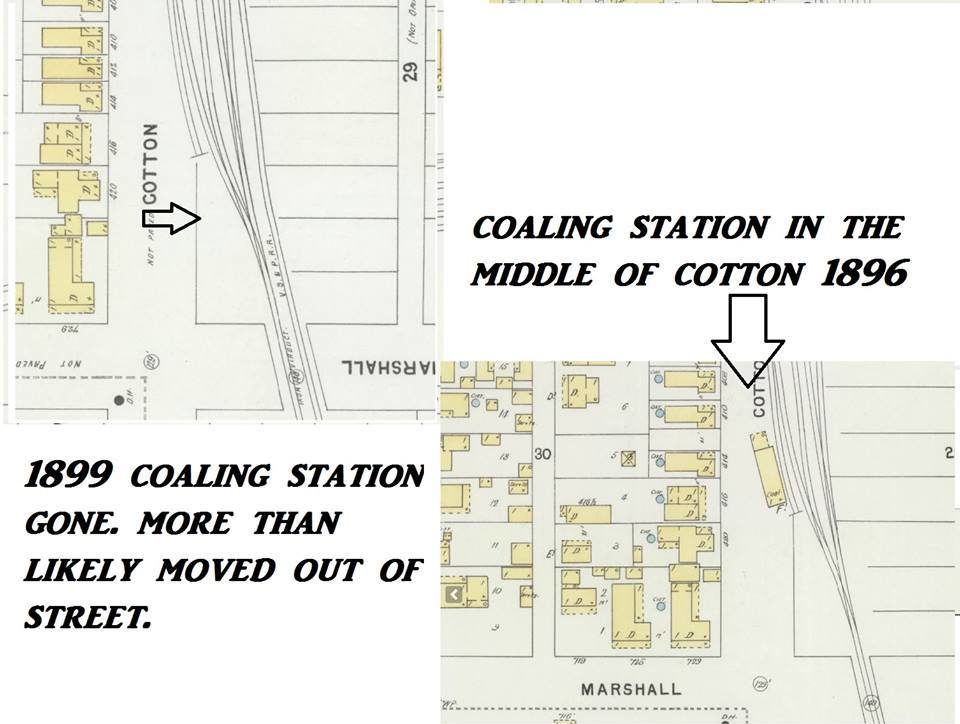

An 1896 Sanborn map shows a coal structure on Cotton Street near Marshall Street.

By 1899, the structure had moved from Cotton Street (this could be why Cotton Street is very narrow in the 400 block).

Subsequent photos show a structure adjacent to Cotton Street.

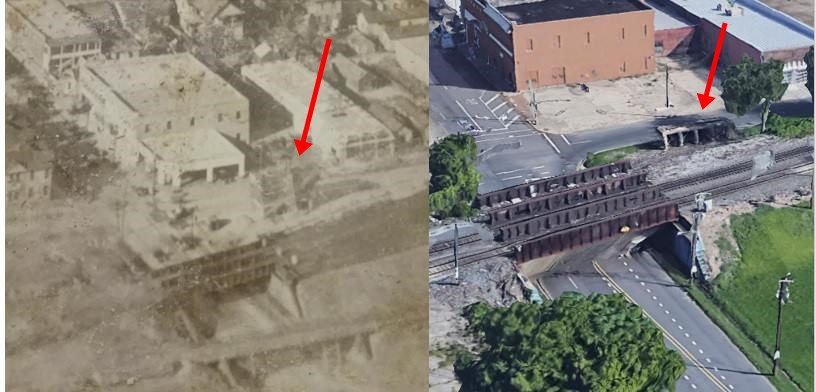

This photo shows the then- and now- photo for reference.

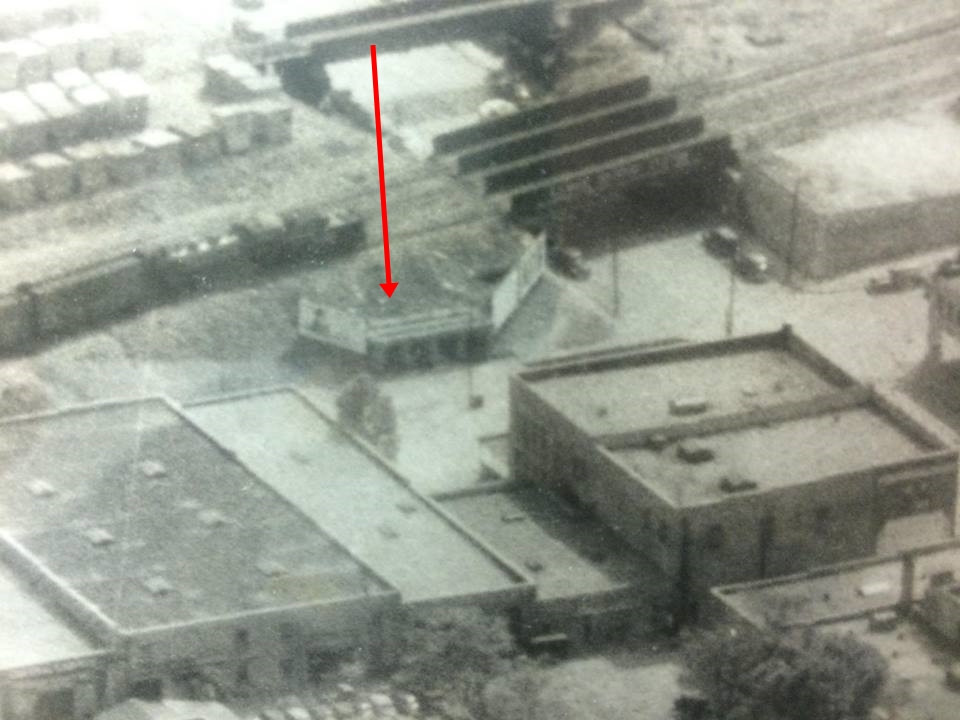

By the time this photo was taken, the structure on top of the columns was gone and billboards lined the area around it.

By the time this photo was taken, the structure on top of the columns was gone and billboards lined the area around it.

Our thanks to those helping keep our remarkable history alive and for their help on this story- Robin Snyder, the Shreveport History Facebook page , Dave Bland of the railroad society and museum, and Marty Loschen with the Spring Street Museum. We encourage you to learn more about our amazing past at the Spring Street Museum, 525 Spring Street, and the Shreveport Railroad Museum and Shreveport Water Works Museum, 140 North Common Street. All are free and will reopen after the COVID-19 shutdown order is lifted.